The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Last week I got to visit a building of great significance for our faith, in Israel. The church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or of the Resurrection is simply much more than a church, it is a shrine of all traditions, it is not a shrine to a particular saint or martyr who devoted his or her life to Christ, it is a shrine for all Christians, in which all that divides and unites Christians at the same time co-exists, it is a shrine of all denominations, it was a shrine of the many Churches, it was a shrine when the Church was one, it was a shrine when the Churches were many, it was a shrine when the Church began at Pentecost and it was a shrine to the apostles and relatives of the human, God made manifest, the Christ, the Son. It is not a shrine of relics, the real meaning of this shrine lies in its origins; it was the Calvary and the tomb of Jesus, a middle-aged man, born of Mary in Bethlehem and who lived in Nazareth, here he was wept for three days. On the third day, he was here no more, this is a shrine to the resurrection and to that expectancy of heaven and our final salvation. It is the crucifixion and the resurrection, the link between what is tangible and what is above, where the strife was over and the battle done.

Calvary and the Tomb, Biblical References

We do not know much about the site of the church before the conversion of Constantine, soon after Jerusalem was destroyed by Titus, Christians fled beyond Jordan, temples and forums were built on the site. Before the resurrection was the crucifixion and the four canonical Gospels say that Christ was crucified in Golgotha, which is, the place of skull (Mark 15:22) and that the Sepulchre was nigh at hand (John 19:42). Golgotha, the Greek transcription of an earlier Aramaic word means exactly that, the place of the skull. The Gospels of Matthew and Mark refer to the Calvary as the place of the skull, that of Luke refers to it as the place known as Skull, that of John instead refers to it as the place of the skull, known as Golgotha. The evangelists do not refer to the Calvary as a rock or a mount, but they refer to an area in which Jesus was crucified that was named so, it was located outside the city wall (Hebrews 13:12, Matthew 27:39, Mark 15:29). Cyril of Jerusalem instead refers to the entire area as Martyrium, other chroniclers of the time, including Theodosius in the De Situ Terrae Sancte, will refer to it as the Calvary by the time of Constantine. Later on, Calvary will only refer to the stone of the crucifixion, within the area. An important observation is that during Jesus’ times this area was also used as a cemetery, with Jewish tombs, of Herod’s time, of the kokim kind (rather small), including the famous hypogeum of Joseph of Arimathea - Jesus’ tomb was of this kind. The Gospel of John gives more information: at the place where Jesus was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb, in which no one had ever been laid. Cyril of Jerusalem recalls remains of a garden by the Constantinian basilica, perhaps of Pagan origin. Romans always used the same spots for capital executions, such as the Esquiline Gate in Rome, and it is plausible that they generally used Golgotha for that purpose. It is even possible that it was the same spot that is referred to in the Book of Jeremiah. It is almost obvious that there was a garden because the area was right outside the Gardens’ Gate, at that time, outside the walls. The four Gospels all mention that the three crucifixions occurred on the same day, and given accounts of the time and the idea that crucifixion had to set an example, it is plausible to think that it happened on the highest spot of the mount, an old Iron Age quarry, so that many could witness and remember. Further proof of the validity of Jesus’ tomb are found in the descriptions of the tomb of Joseph, in Matthew 27,60 - Mark 15,46 - Luke 23,53; it was an ante-chamber one could enter without the need of entering the tomb, in John’s testimony of the resurrection he mentions that he had to kneel to look inside (John 20,5). These kinds of tombs generally had a round stone as a door. In this small tomb, and on its stone Jesus’ veils were laid (Luke 24,12 - John 20,7).

Ancient Symbolism, The Tomb and the Skull of Adam

One of the most common characteristics of Christian iconography and that any museum addict or amateur art historian, or even Sunday school child, might have noticed, is that in many representations of the Crucifixion of Christ, from Byzantine icons to Giotto, from Hans Memling to Guido Reni, there always seems to be a skull and sometimes even scattered bones at Jesus’ feet, below the Cross. This has nothing to do with representations of death or resurrection or any artist’s creepy strike. It has a lot to do with what the Calvary was thought to be before Jesus. According to an ancient tradition, Jewish and then Christian, the so-called tomb of Adam was located on the Calvary, right under what will become the site of Jesus’ crucifixion. Adam’s body was retrieved by Shem and Melchizedek, from Noah’s Ark, and then the angels led them to bury it in Golgotha, in a very deep cave, where the head of the serpent from the Fall of Man could still be seen. This legend became extremely popular beginning in the 4th century, and it was thought that this was why it was known as the place of the skull. St. Jerome will deny this in 398, explaining how Golgotha really just meant a place of execution. Another legend states that it was moved there by divine providence. Today, one of the oldest chapels of the Holy Sepulchre is that of Adam, where a a crack in the rock would show how the earth shook at Jesus’ death, redeeming even the first sinner, buried there when the blood of the Saviour ran over the skull, through the rocks on the skull. The crack in the rock is still visible.

The Question of “Without a City Wall”

There is a green hill far away, without a city wall, where the dear Lord was crucified, who died to save us all are the words of a popular Anglican hymn for Good Friday by Cecil Frances Alexander, and it poses a question that had been taken for granted for quite a long time; if the green hill is without a city wall, why is it inside it? Recent and not so recent research has been wondering why is the church of the Holy Sepulchre quite far inside the city walls if burials could only take place outside the city? Could it be false? This has been source of endless literature and speculation but we can finally answer this old dilemma. It is known that Jesus was crucified outside Jerusalem, not far from a city gate, but in the vicinity of a street, on the Golgotha, the place of the skull, thankfully these instructions limit our area of research. So was Golgotha, now the spot where the church is outside the city walls then? Was there a city gate there? Were there gardens and tombs? During the siege of Jerusalem of 70 A.D. under Titus, it is known that the Romans took the three series of walls of the city, however, during Jesus’ time, only two walls existed, because the third was built by Agrippa (41-44 A.D.) and not even completely, and in the north sector of the walls, there were never three of them. Archeology in Jerusalem is extremely difficult because of the city’s rough history and because it is so densely populated it is never quite easy to make extensive research. We know that the first wall, from the Kings’ Era, would connect to the Temple and now surrounds the former Ottoman citadel through an impressive viaduct, departing from the Tower of David. The modern Bab es-Silsileh street and the minaret are on the former side of the old wall. The second wall started from the so-called Gennath gate which was in the first wall, and was located only along the norther part of the city, until the Antonia Fortress. It is here that possibly was also the Gardens’ Gate, which could also be the Corner’s Gate of the Scriptures, outside which was the Golgotha, then an area with gardens and tombs, therefore outside the city walls. The third wall doing to the time of Herod Agrippa was to be found in the norther part of the old city. We have every right to think that the Holy Sepulchre church is indeed to be found outside of the city walls of Jesus’ time which are now found within the third walls built in 41-3 AD. The memory of the site also remained because the local community kept worshipping there, and in 135 Hadrian built his Capitoline temples of Venus and Jupiter there, levelling the top of Mount Calvary, this was part of his policy of keeping Jews and Christians out of Jerusalem after the Jewish insurrections.

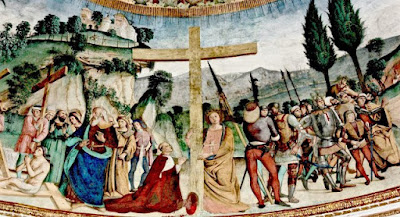

The Exaltation of the Holy Cross, the Role of Helena and Constantine

In Christian iconography Saint Helena is often depicted holding a cross because according to tradition it is in Jerusalem that she found the relics of the true cross. She was the mother of Emperor Constantine, who sized power in the year 312 and in 313 made Christianity legal through the Edict of Milan. They both converted. At the age of about 60 she went to Syria Palestina in search of the sacred sites of Jesus’ calvary, around the year 324, funding churches marking the place of the Nativity and the Ascension. Eusebius of Caesarea noticed how she also particularly took care of the poor; donating alms and freeing prisoners. At the same time she adorned houses of prayer with rich offerings, from the largest to the smallest cities. Around year 326 the temple of Jupiter was demolished and excavations found the supposed tomb of Jesus. The temple of Venus was also demolished, exposing the site of the crucifixion, according to the Medieval chronicle of saint: the Golden Legend, Saint Helena, legend goes that a local Jew named Judas knew where the crosses were located, they found them, including the titulus (Jesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum) in a rock-cistern, but then the question of which one was Christ’s arose; they brought a dying woman to the spot, she was made touch each of the three crosses, the last one healed her and the true cross was identified. According to St. Ambrose, St. Helena uttered the words: she worshipped not the wood but the King, Him who hung on the wood. She burned with an earnest desire of touching the guarantee of immortality. Most of the relics were kept in Jerusalem for adoration and liturgies, others were sent to Rome. Saint Helena commissioned the foundation of a new church on the spot.

In 326, Constantine ordered the laying of the foundations of a new church of splendour worthy of its richness and to re-institute both to sight and venerations all the holy places of the Lord’s Resurrection. The Emperor ordered to edify a church building that while he levelled the original area, as he did for St. Peter’s in Rome, he also tried to maintain the original geography of the crucifixion and Sepulchre sites. The Constantinian building followed a longitudinal axis, from west to east; within this complex we could identify four main elements: a rotunda, a basilica, two courtyards and a portico. The tomb was modelled to look like an aedicola, it was a the heart of the complex, its decoration was rich and it was covered with a dome. It was later named Anastasis (resurrection). The other part of the complex, named Martyrium was a basilica with five naves in the style of those at Rome. Three doors opened to a monumental staircase that led to a portico. Beneath the church was a crypt with St. Helena’s Chapel, containing the true cross’ relics. The Constantinian church was decorated with columns, mosaics, polychromed marbles, no art was spared to make it beautiful. Sadly, the glorious building was burnt down in 614 by the Persians.

The Destruction of the Church, the Byzantine Church, the Remodelling of the Site

The church was restored by Modest of Jerusalem, a Byzantine patriarch. However, in 1009, the building was almost completely destroyed by Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, also known as Nero of Islam, and later, in 1033, by an earthquake. Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos, outranged, ordered its restoration. Hakim’s successors will be more tolerant of the Byzantines and will allow the reconstruction and the decoration of the church. At a great expense of the emperor and the Byzantine patriarchs. Debris were removed quite quickly, the original plan of the complex could still be individuated, the Sepulchre and the Golgotha were damaged but relatively intact. The construction of the new Byzantine church began in 1042, rebuilding the architecture that held together the most important sites of Christianity. The new construction was centred around the rotunda, the atrium and the basilica were lost, with chapels surrounding it. It was much more “compact”. The entire base of the church had to be rebuilt. It is with the Byzantine reconstruction that the original configuration finally disappeared. The portico was kept and become an area of preparation before the Sepulchre. The Golgotha rocks were surrounded by a marble flooring. Later an apse was added to the rotunda, developing it into a church.

The Rotunda: Symbolism and Echoes

The rotunda is found at the heart of the Anastasis, it contains the Holy Sepulchre itself. The Anastasis holds two rooms; the first holding the Angel’s Stone, a fragment of the tomb that sealed the tomb, the second being the bomb itself. The rotunda is located at the centre of the Anastasis, beneath the largest dome. It is decorated with a 12-pointed star, whose rays symbolise the outreach of the 12 apostles. Interestingly, perhaps what is Jerusalem’s most renowned landmark, the Dome of the Rock, was built following exactly the same structure and measurements.

The Effect of Islam

Throughout the centuries, especially after its destruction and reconstruction during the Middle Ages, the Holy Sepulchre suffered greatly in different ways, because the resurrection of Christ, who is a prophet in Islam, is not accepted. A Muslim monastery erected by Saladin in the 11th century, worked on essentially nullifying the effect of the church by building two minarets by the Sepulchre. We can probably say that the effect of Islam on the church building was varied; whereas originally the early churches were almost completely destroyed, after Saladin’s victory and the Muslim reconquest of Jerusalem, the church was somewhat safe, pilgrimages were still allowed. Unfortunate events regarding Islamic iconoclasm, deprived the building of its series of magnificent mosaics and marbles.

The Crusaders’ Church and its Significance

On 15 July 1099, the First Crusade, ordered by Pope Urban II, captured Jerusalem once again. It was considered an armed pilgrimage, each crusader would revere the Holy Sepulchre once in Jerusalem, it is said that the first ones to arrive wept and sung a Te Deum. When Christianity was restored in Jerusalem, the new Crusader State became officially the Kingdom of Jerusalem, its first monarch being Godfrey of Bouillon. The first King of Jerusalem, refused the title and initially only adopted that of Defender of the Holy Sepulchre, Advocatus Sancta Sepulchri. Therefore, during the Christian rule in the Holy Land, this became a sort of Westminster Abbey, a royal church. This does not have to scandalise use, often in Rome I am teased about our Anglican Church having been founded by a King who wanted a divorce, truth is this relationship between monarchy and religion is older even than Christianity itself: if we think of Constantine and Theodosius, Byzantine and Holy Roman Emperors appointing Bishops, Kings being anointed to minor orders, just like the Queen today. This is simply another fruit of the special relationship that especially during the Middle Ages linked religion and monarchy. One of the first questions of the Crusaders was to rebuild the church of the Holy Sepulchre. The question was whether to restore the heavily damaged Byzantine church or to build a new one altogether. A compromise was reached in the end; the idea was to unite the tomb and the Golgotha under one building, while securing the access to the lower crypt of St. Helena. Construction ended on 15 July 1149. Only an inscription, once on the mosaics of the Calvary Chapel confirms the reconsecration of the church in 1149. The new church, even smaller than the Byzantine one, was built in a transitionary style between the late Romanesque and the early Gothic. By the rotunda was the new church, that was now reduced to the quire, a transept with a dome, and an ambulatory, with three chapels; the Greek Chapel of Saint Longinus, the Armenian Chapel of Division of Robes and the Greek Chapel of the Derision - along the ambulatory is also the high altar, east of which is an Orthodox style iconostasis dividing the sanctuary from the nave.

The Chorus Dominourm, the quire is a fascinating part of the building, built on the former portico and on two levels sustained by Romanesque pillars, it gives access to both the rotunda and the Calvary. The original Byzantine apse was removed and was replaced with a great arch which opened the space within the complex. During this restoration the altar was moved from the center of what was now the quire, to its east end. There were therefore two liturgical poles within the church; the altar, where the Eucharistic sacrifice was held, and the tomb, where the miracle of the resurrection occurred. Under the Crusaders, the Calvary chapel ceased to be isolated and was made more of an integral part of the spiritual experience of the church, by enlarging its asset. Through a staircase one could have access to the below Chapel of St. Helena, divided in three naves, with its focus on the chapel of the true cross, in what was the crypt of the Constantinian basilica. Once the portico was closed, it was necessary to emphasise the south façade which remained the only access to to the pilgrims. It is in the Romanesque style, including the bell tower, and it has a great portal though with a very small door and it grants access to both the church but also directly to the Calvary through a staircase. It is located on the Via Dolorosa, alongside several Christian chapels of various Eastern Rite Churches.

Different Christian Churches, one Building

With the Crusaders came also the Latin rite to the Sepulchre, in 1555 the Franciscan friars arrived and despite the Muslim and then Ottoman Rule which lasted until the British Mandate of Palestine, a question arises? How did Western and Eastern Christians share such a sacred space despite the differences? The question is known as the Status Quo. A Sultan’s decree of 1853 defined custodians and the different roles of each denomination. The primary custodians being the Greek Orthodox, the Armenian Apostolic and Roman Catholic Churches, with the Greeks having the lion’s share. The Copts and Syriac Orthodox also have a small share, although the first are banished to the roof., a staircase leads to their chapel These responsibilities include shrines and chapels within or outside the building. The Greeks operate under the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre and the Franciscans through the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land. However, the Status Quo did cause unpleasant consequences; for example times and places of worship are strictly regulated in common areas but that is often not respected, sadly particular situations can abrupt into violence. In 2002, on a hot summer day, a Coptic monk moved his chair into the shade and this was interpreted as a hostile act by the Ethiopians and 11 people were hospitalised as the situation degenerated. In 2004, during Orthodox celebrations of the Holy Cross, the Franciscan Chapel was left open and it was taken as a sign of disrespect; a fight ensured. On Palm Sunday 2008, another brawl broke out because a Greek monk was ejected from the building by rivals. Later that year, another clash erupted with the Armenians around the Feast of the Holy Cross. These unpleasant situations have been going on for centuries and a sign of this is a wooden ladder placed over the church’s entrance in 1852, when it was defined that the entrance was common ground, the “immovable ladder” remains there to this day to show the delicate situation of the Status Quo. Because the entrance is common ground, each day the opening and closing of the church is a complex ritual. The custody to the door and keys is entrusted to two local Muslim families. Back in the 13th century the local Sultan assured Pope Innocent IV that he would repair any damages following the Khwarezmian invasions, and that he would entrust the keys to two Muslim families. The tradition continues to this day at the original Medieval wooden door. There are two manners of opening the door: a simple opening and a solemn opening, in the second case the door is fully opened.

Ultimately, this building scarred by conflict is a reflection of our world, waiting for the reconciliation that Christ the Lord will bring again through his sacrifice of blood and his glorious resurrection. It is in this very church building that our differences come alive, even around such a symbolic place, where death and the rebirth of the flesh have occurred, at the Golgotha and at the Sepulchre. During one of my visits, the Franciscans friars played the organ during Mass, the touching notes of that familiar instrument married perfectly with that glorious space, at the same time, the Greek Orthodox responded to the "noise" by ringing the bells, that might have been a conflict, but for this pilgrim it was an ethereal and ascetic experience. Even in conflict Christ repays us with beauty. Here we are recompensed with a vision of what is to come.