St. Paul's within the Walls, an American Episcopal church in Rome.

Ever since the beginning of the early 18th century British Anglicans had been coming to Rome during what was then known as the Grand Tour, when affluent young men and women were sent to Italy to learn about the art and history of the Classical and Renaissance world of which Italy had been the epicenter, and to mingle with the local aristocracy for decadent yet fancy social events.

These young Anglicans sometimes brought with them copies of the Book of Common Prayer for private worship, as non-Catholic public worship was still illegal within the city walls at the time. Throughout the Papal States, it was still not seen in a good light. The first official Anglican act of worship, a service of morning prayer, took place in 1816, in a tiny apartment in the Via dei Greci, near the present Church of England parish of All Saints’ on the Via del Babuino, much like in the early Church, services began to take place in private apartments and foreign legacies, until a Chapel was finally granted for Anglican use outside the Porta del Popolo in the mid-19th century.

With the settling down of the Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars ("1812" for the Americans) - affluent Americans of the upper crust began to travel themselves to Italy, coming from a nation built in neo-classical architecture and living in a political system fashioned around the foundations of the ancient Roman canon - they began to flock to Rome from the late 18th century to early 19th century, they began the American Grand-Tour.

The Spanish Steps in a late 19th century photograph.

The first official Episcopalian service was held in Rome in an apartment in the "English Ghetto" of Rome, near the Spanish Steps, in 1859 - it was a service of Holy Communion, led by Alonzo Potter, the then Bishop of Pennsylvania. That same year the Rev. William C. Langdon arrived in Rome with the purpose of forming an American church. The first service was held on 20th November, and after two days, the American community of Rome decided to form a church community, an Episcopal church, being that the de-facto national Church of America, and having been the historical home of many presidents, dignitaries, and cultural figures, to this day. The community became known as Grace Church, Langdon was elected as rector by the vestry the following year - in 1861, the American Church recognized the community as part of its own and like for the English, a former granary was given to them outside the Porta del Popolo for use as a chapel. Grace Church, the first Episcopal church in Italy, was formed.

However in less than 10 years, Italy became a unified nation and the temporal power of the Popes over Rome ended, thus allowing non-Catholics to build houses of worship within the city walls. That same year, in 1870, after two weeks from the establishment of the new regime, the vestry met to discuss the building of a new church. In 1872 land was purchased near the Quirinal Palace in what used to be land belonging to Cardinal De Merode, the Papal secretary of war, which then passed to a nunnery and then private owners. Funding for the building of the new church was raised quite quickly, but was soon redirected to Chicago in the light of their 1871 fire.

Within the next year, generous donors made sure that twice as much as needed was found. That was thanks to the help of the great Episcopalian tycoons of the Gilded Age, that includes names such as J.P. Morgan or the Astor Family, also donors of some of the greatest Episcopal churches of Manhattan, and both also visiting Rome very often - Morgan having founded the American Academy, and William Waldorf Astor working in the diplomatic scene, and both being deeply involved in the local social scene of the time. The American Gilded Age, was in a way, a new Renaissance - great family names like the Morgans, Vanderbilts or Astors, (think of the Medici or the Gonzaga in Italy), gained power and affluence, and in order to establish themselves as more than just new-moneyed Americans, they used the power of patronage and philanthropy, much like their predecessors, to found churches like Grace Church Broadway or St. Paul’s Rome, cultural foundations like the MET, or beautiful houses like the Isabella Gardner House in Boston, the Frick Collection or the Morgan Library in New York - accumulating beautiful art from the past while commissioning some newer.

Grace Church changed its name in 1871, as the name “Grace” in Italian is only strictly relatable or associable with Our Lady. Grace Church became St. Paul’s within the Walls. St. Paul himself lived and preached in the nearby area, so the choice was spot-on! St. Paul’s first rector, was very much a fruit of the Gilded Age - the Rev. Dr. Robert J. Nevin, was an avid collector of late-Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque art, as well as a known socialite in Italy, Britain and America. He commissioned St. Paul’s to be built in a shape that would not contrast with the surrounding Roman landscape, and decorated in a way that would have shown the Roman Catholics that other forms of Catholicism existed, a Reformed Catholicism - his life remained in danger while in Rome from the attacks of religious fanatics. Nevin’s collection, catalogued by Italian art historian, Federico Zeri, was phenomenal - it included early Renaissance pieces by Paolo Veneziano and Carlo Crivelli, as well as a Baroque painting by Luca Giordano. The rectory he commissioned to George Edmund Street, still in use today, was an eclectic take on a Venetian palazzo, and it was richly decorated with ancient pieces of marble, neo-classical fireplaces from the demolished Palazzo Torlonia in the Piazza Venezia - it came with a library, a ballroom and even a gallery. It was the ideal Gilded Age dream where a rector could entertain his guests.

On 5th November 1872, ground was broken for the foundations of the new church. During excavations various ancient artefacts were found, among them some three large Roman vases (or oil jars) - one of them can still be seen in the garden at St. Paul’s - the other two went to America, one is in the garden at Grace Church in Broadway, making it Manhattan’s oldest piece of public art, the other one is in the Newport villa of Catherine Lorillard Wolfe, a great donor of St. Paul’s and New York philanthropist, who thought it would have looked quite attractive in her garden. The design of the church went to renowned British ecclesiastical architect George Edmund Street, who had already gained considerable fame in England, for his rediscovery of Italian Medieval architecture as seen in the light of the new High Church revival of the 19th century.

A late 19th century print of St. Paul's within the Walls.

On the Feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul, on 25th January 1873, the corner-stone, an actual stone taken from Independence Hall in Philadelphia, was laid on the Via Nazionale ground. The church was completed three years later. The church was consecrated on the Feast of the Annunciation, the 25th March 1876 - celebrations lasted for a week and despite the lack of a pipe organ - the music proved to be great, the first organist and choirmaster of St. Paul’s was Dr. E. Monk of York Minster who directed the choir masterfully, a choir mostly made up of ladies and gentlemen from the Anglican English and American congregations, to whom Dr. Nevin extended his praise in his minutes. The music was great; at Mattins, the Venite and Psalms were set to Anglican Chants by Tallis, Monk and others - the canticles were by Boyce, Gilbert and Foster. At Communion, the Mass setting was Tuckermann in C, the anthem “Praise the Lord, O My Soul” by John Goss. The American Bishop of Long Island was there to lead the service, accompanied by the missionary Bishop of South Dakota, the British Bishops of Gibraltar and Peterborough were present, as well as the Irish Bishop of Down and Connor. The English Chaplain of Rome was also present to bring the support of St. Paul’s sister Anglican congregation in Rome. Celebrations lasted for eight days, and all the bishops present, preached at different services.

A 19th century Italian print of the service of consecration of the church.

During the Great War, St. Paul’s rector was the only English speaking minister in Rome - despite the high number of servicemen in the city. After the war he took responsibility for the refugees and orphans. During WWII, in 1940 St. Paul’s was closed and placed under protection of the Swiss Legation in Rome, like its sister church of All Saints’, but not before its rector, the Rev. Hiram Gruber Woolf, was arrested by the Fascist authorities for having flown the American Star Spangled Banner from the Rectory and having had the carillon playing American patriotic songs rather loudly - he was then interned in a Nazi concentration camp. St. Paul’s reopened as a chaplaincy for American troops in 1944, the rudimental pews, still used today were built by the quartermaster corps from a stockpile of pine words originally meant for cheap wartime coffins.

The post-war period for St. Paul’s was a time of reorganization and repair after the neglect of wartime, it was time to stabilize the finances and rebuild the congregation. The then rector, the Rev. Charles A. Shreve, did exactly that. During his tenure St. Paul’s became a hub of Dolce Vita enthusiasts who came to Rome for one reason or another, he was friends with Henry Fonda, and his children, including Jane Fonda, who worshipped at St. Paul’s many times, Gloria Swanson, Olivia DeHavilland also became parishioners while in Rome. Ambassador Clare Boothe Luce also became a member of St. Paul's. President Eisenhower also joined St. Paul’s for Sunday morning worship while in Rome in 1959. Shreve was completely immersed in the social scene of the Rome of the time. The late Peter Rockwell, a sculptor and son of American artist Norman Rockwell was a parishioner well into the late 2010s - he was also churchwarden at various times throughout the church's history.

St. Paul's during the Liberation of Rome.

The post-war period for St. Paul’s was a time of reorganization and repair after the neglect of wartime, it was time to stabilize the finances and rebuild the congregation. The then rector, the Rev. Charles A. Shreve, did exactly that. During his tenure St. Paul’s became a hub of Dolce Vita enthusiasts who came to Rome for one reason or another, he was friends with Henry Fonda, and his children, including Jane Fonda, who worshipped at St. Paul’s many times, Gloria Swanson, Olivia DeHavilland also became parishioners while in Rome. Ambassador Clare Boothe Luce also became a member of St. Paul's. President Eisenhower also joined St. Paul’s for Sunday morning worship while in Rome in 1959. Shreve was completely immersed in the social scene of the Rome of the time. The late Peter Rockwell, a sculptor and son of American artist Norman Rockwell was a parishioner well into the late 2010s - he was also churchwarden at various times throughout the church's history.

St. Paul's in a late 19th century photograph.

During the 1960s and the 1970s the church celebrated the Second Vatican Council with a liturgical rearrangement of the sanctuary and the commission of two bronze doors celebrating the new ecumenical movement. The basement became an alternative Cultural Center for students and artists, the crypt became a place for American teenagers and young adults to hang out. In the 1980s St. Paul’s began to prepare to launch itself into the new century and millennium by opening a refugee center, now known as the Joel Nafuma Refugee Center, founded in 1984, and by opening its doors to Rome’s Latin American community in the early 1990s for a Sunday Eucharist in Spanish. Today, under the leadership of Fr Austin Rios, St. Paul’s continues to maintain its call as an Episcopal Church parish in Rome by growing as a dynamic and welcoming community, there are fundraising activities for the ever successful refugee center, weekday worship, often followed by fellowship, such as the Compline, Soup and Bible study event every Wednesday, as well as new opportunities to enjoy its amazing musical scene, like the Advent Carol Service, and most recently also the celebration of Choral Evensong. St. Paul’s success is probably rooted in its dynamic and realistic approach to the modern world’s changes and necessities, while functioning as an active church community. A high fruit of the Gilded Age and the Grand Tour that manages to stay relevant despite the changes and chances of this fleeting world.

A contemporary photograph of the interior of the church.

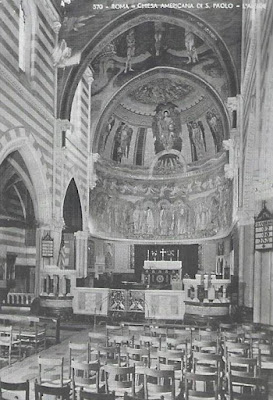

However, its crowing jewel is certainly its art. When St. Paul’s was built, Dr. Nevin, a connoisseur of beauty, spared no expenses (even at the expense of his own salary) to transform St. Paul’s into a triumph of Anglican art rooted in the local Catholic language. The building, designed by G. E. Street, probably being his most unique work, was inspired by Northern Italian architecture, and especially by the basilica of San Zeno in Verona, as we can see by the similar vault, and the same polychrome motif of the brickwork. The tiles in the aisles are by Frederick Garrard, a Victorian artist. The interior is rather fascinating as well, originally, the quire followed the scheme of an early-Christian schola cantorum, with two pulpits on either side, one for the Gospel and one for the Epistle - with the quire being designed in the traditional Anglican style, enclosed by a marble gate, with brass “peacock” gates, reflecting the motifs in the mosaic above, and finally finding its apex in a beautiful high altar, decorated with embroidered frontals, some of which still survive today, and raised by a few steps, then topped with a cosmati gradine, now part of the episcopal chair base. The beautiful episcopal throne itself was given as a gift by the English church in Rome as a sign of friendship between the two Anglican congregations. The pulpit baluster is in green, white, and red marble to honor the Italian flag, so were also the now gone sanctuary steps. The sanctuary still has the three seats for subdeacon, celebrant, and deacon. The side chapel, dedicated to Saint Augustine of Canterbury hosts a fine early Christian cross, the sacrament is reserved there - the two brass crosses for the high altar and chapel are now to be found in the Library.

A late 19th century photograph of the interior of the church prior to the installation of the lower cycle of mosaics by Burne-Jones, and with the three lancet windows still in place.

The sanctuary was rearranged in the 1960s to accommodate the new liturgical style in the light of the recent ecumenical movement. The church boasts two baptismal fonts, an early Medieval one of Roman manufacture, and a Victorian one. The bell tower has the largest playable carillon in Rome, while the rectory, also by Street, is an eclectic take on a Venetian Palazzo. The stained glass windows tell the story of the life of St. Paul, and like the ones at its sister church of All Saints’, were commissioned to the English firm Clayton&Bell of London. In the original project by George Edmund Street, the apse featured three lancet windows, with Christ in Glory in Heaven, and other scenes from his life - they were moved ca. 1894 to make room for the other Burne-Jones mosaics, they are now beautifully framed in the parish hall.

The mosaics in the counter-façade and in the façade were only added in the 1920s by George Breck, then director of the American Academy in Rome and friend of J. P. Morgan. They represent the Nativity, Adoration of the Shepherds and of the Kings, in between the holy cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem, above the rose window is the hand of God the Father in the act of Creation. On the façade, around the rose window are the four evangelists, while over the west entrance door there is a further mosaic of St. Paul preaching in Rome.

A 1930s photograph of the interior of the church with the original arrangement of the sanctuary.

The counter-façade with the Breck mosaics.

Perhaps St. Paul’s real crown jewels are the stunning mosaics commissioned by Dr. Nevin to renowned English Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir Edward Burne-Jones, who was friend with G.E. Street, first for the upper section of the apse, and then for the entirety of the apse and the quire. The mosaics, paid for with Morgan money, are so fine that they have been designated a National Monument by the Italian Government. The cartoons for the mosaics by the artist still exist in the rectory at St. Paul’s. The Pre-Raphaelite movement started in 19th century Britain as part of the Arts&Crafts movement as a post-Romantic call back to the Italian art of the late Gothic style and the early Renaissance style, part of it was also religiously inspired, as shown in the writings of John Ruskin - Burne-Jones was part of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and in the first Pre-Raphaelite wave, St. Paul’s is perhaps their crowning jewel outside of Britain, especially in the light of the courageous cultural dialogue it was putting itself into.

A contemporary photograph of the nave looking towards the sanctuary.

On the first arch, above the quire, is a peculiar representation of the Annunciation based on an early legend (and using an iconography Burne-Jones used again and again) in which Mary is seen drawing water from a spring when she sees the Archangel Gabriel greeting her. The reddening colour of the skies signifies it’s the time of the Angelus (6.00 pm). In the left-hand corner there is a pelican, a Medieval symbol of Christ, peaking its breast to feed its hungry young. Under the scene is the greeting from Gabriel: “Hail, thou that art highly favored, the Lord is with thee” (Luke 1:28) and Mary’s answer “Behold the handmaiden of the Lord; be it unto me according to Thy word.” (Luke 1:38). On the second arch above the quire, Burne-Jones represented the Tree of Forgiveness, Christ is outstretching his arms while being suspended before the green-leafed Tree of Knowledge between Good and Evil. The thistles from which spring lilies symbolise the Annunciation. Under this scene is written in Latin: “In the world, ye shall have tribulation, but be of good cheer, for I have overcome the world.” (John 16:33).

Detail of the Christ in Glory mosaic by Edward Burne-Jones.

In the great mosaics of the rear wall of the apse, is Christ in glory, at the top is a blue vision of heaven with a glimpse of the choirs of angels. Below is Christ seated in majesty, enthroned in between Cherubim and Seraphim, on the left hand, he’s holding a transparent orb, while he’s in the act of blessing with his right hand. From his feet are the four streams of living water from Revelation, as well as the rainbow, that is “round about the Throne.” (Revelation 4). On either side of Christ are the archangels, each standing before a gate of heaven, one is empty, that would have been Lucifer’s. Below is the sea of firmament, broken by an inscription in Hebrew which reads: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.” (Genesis 1:1) and one in Greek: “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God.” (John 1:1). Below, is a series of angels, much like the sheep representing the apostles in early Christian mosaics, dividing the two halves of the mosaics, although here the angels are separating heaven and earth, in the lower register, we have the saints, the Church Triumphant.

Detail of Saints in the mosaic by Edward Burne-Jones.

Against the background of the Heavenly City, we have the five traditional group of saints, on the left are the ascetics, the prophets of the Church, such as Saint Francis of Assisi, then are the matrons, representing the service of God in ordinary life, among them Martha with her keys and Mary Magdalene with the holy oils. The major group at the center represents the great figures of the Church’s past, five fathers from the Western Church, and five from the Eastern, with Saint Paul in the front, wearing a chasuble. To the right are the Virgin and Saints, among them: Saint Catherine, Saint Barbara, Saint Cecilia, Saint Dorothea, and Saint Agnes. Finally on the right are the Christian warriors, Saint George, Saint Andrew (holding their shields respectively, representing the origins of the American Episcopal Church), Saint James, Saint Patrick and Saint Denis. Again, following the philanthropic heritage of the Renaissance, Dr. Nevin, commissioned these saints to also represent contemporary figures of the time, among them, Junius Morgan (Father of J. P. Morgan) who helped paying for the mosaics, Archbishop Tait of Canterbury, General Grant, Giuseppe Garibaldi, and Abraham Lincoln. One would think that Dr. Nevin went too far in trying to imitate a Roman church, but while that was true for aesthetic reasons, they also went very close to portraying the Pope in the mosaics as the anti-Christ!

Detail of Saints in the mosaic by Edward Burne-Jones.

St. Paul’s today is a welcoming and dynamic community, with amazing qualities in outreach and charitable work, housed in one of Anglicanism’s most beautiful buildings, if you’re visiting Rome, make it part of your list of things to see. It is truly unique.

Detail of the exterior view of the rose window with the Breck mosaics representing the four evangelists.